I have often wondered whether older books of general knowledge and quiz books were designed to inform and test their readers or to highlight the apparently superior intellect of the writer or compiler. Certainly Hubert Phillips's contribution, Who Wrote That?, succeeds in making me feel tantamount to illiterate and while I would like to think that his quiz, "containing 400 well-known and not quite so well-known quotations" is merely difficult because times and tastes in writers change, I fear another response may be the more plausible.

Who Wrote That? is, or was a Penguin yellow-back original published in 1948 and numbered PT5. The author whose somewhat self-satisfied photograph adorns the back cover is described (or self-described) as, "one of the most versatile, as well as one of the most knowledgeable, of contemporary journalists." As well as serving as bridge editor, crossword writer and quondam principal leader writer of the News Chronicle we are informed he had also been Head of the Economics Department in Bristol University and 'Theme Convener of the Lion and Unicorn Pavilion at the Festival of Britain Exhibition' (I assume the 1924/5 Wembley one). Wikipedia sees him as primarily a bridge player.

So to the quiz itself. Who, for example, wrote, "For all sad words of tongue or pen, The Saddest are these: 'It might have been'." The answer, is John Greenleaf Whittier in something called Maud Muller. Hmm.

Or how about, "The worth of a State, in the long run, is the worth of the individuals composing it." That's John Stuart Mill in Liberty. Fair enough.

Or again, "We carry within us the wonders, we seek without us. There is all Africa, and her prodigies in us." That's Sir Thomas Browne in Religio Medici. I'm not convinced I even know what this means.

Well I suppose I might have got the Mill quotation but if you knew the other two, "You're a better man than I am, Gunga Din". (That's Kipling, by the way).

Who Wrote That? Published by Penguin, 1948. 148pp.

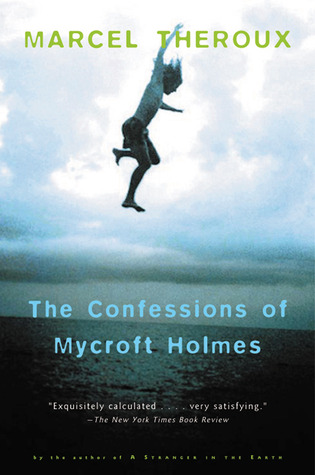

The title led me astray. I had expected Marcel Theroux's second novel to be one of the many that seeks to continue the Holmes saga. After all, among top authors, Michael Chabon's done it, Michael Dibdin's done it and so, indeed, has Anthony Horowitz, so why not Theroux?

Not so. Theroux's tale is a story of brothers. There are five pairs in The Confessions, the least of which are Mycroft and Sherlock particularly since Sherlock, first in a fragment and then in a subsequently discovered and 'reprinted' short story, 'The Death of Abel March' written by the narrator's uncle, is notable by his absence.

But to dwell on Holmesiana is to go in entirely the wrong direction. The core of The Confessions is the relationship between the narrator - the Anglo American Damien March - his father and his recently dead but long forgotten paternal uncle Patrick. And it's the announcement of Patrick's death and Damien's unexpected decision to attend the funeral in Cape Cod, the starts us off.

Patrick and his brother were close during Damien's youth but broke apart in during his adolescence. The former was a briefly successful writer whose natural eccentricity becomes heavily edged with irascibility and whose later years were spent in a house on the fictional island of Ionia off the Cape. The latter, the sort of Englishman best able to be English when in America, is a successful, somewhat anal lawyer. Damien, on the other hand provides the counterpoint occupying a dead-end job in BBC News in London until the news that Patrick's will leaves him the house in Ionia, prompts him to quit and make the move across the Atlantic.

It is in the house, which Damien quickly discovers to be held in trust as a sort of museum of his uncle's bizarre and well-documented collections (ice cream scoops, egg weighers, vitamin pills, mechanical banks), that he finds the Mycroft Holmes story one of whose characters is named for the lost husband of his nearest neighbours.

And having found the story and thought, perhaps too long, about the linkage of the neighbour's name (Fernshaw) to a Victorian martial arts instructor, Damien begins to construct a picture of violence and unexpiated guilt believing that the murder that Mycroft undertakes in the story is a cypher for a murder he considers his uncle to have committed even though no evidence, nor even suspicion, of murder exists.

He's wrong. The truth is at once (slightly) more prosaic and, at the same time unexpected - a fine twist to end an excellent novel.

In constructing this intelligent and clever tale, Theroux is massively indebted to his own impressive ability to describe unusual character and characters with a light touch. Some examples:

Of Damien's father, "In a way, Dad could be properly English only in America, because in England, his kind of Englishness barely existed. Perhaps there is somewhere in the British Isles where people have afternoon tea, bag grouse and talk in Lord Haw-Haw accents but it wasn't in Wandsworth, SW18."

Of Patrick and his story-telling, "Patrick went into more detail about how he used Vitalis to sculpt his hair before a date than Homer did about the armour of the Trojan heroes."

Of his friend, Lloyd, "He always looked tired, like a prisoner who had been kept short of sleep and food to render him submissive. It was as though Lloyd was afraid that if it were contented and well rested, his body might make plans to escape from him."

Oh, and I forgot to mention the quirky and unexplained phrase of Patrick's that echoes through the narrative at accented moments: 'Bolder than Mandingo'. Follow that.

The Confessions of Mycroft Holmes, first published in 2001. A Harvest Book - Harcourt Inc. 216pp in paperback.