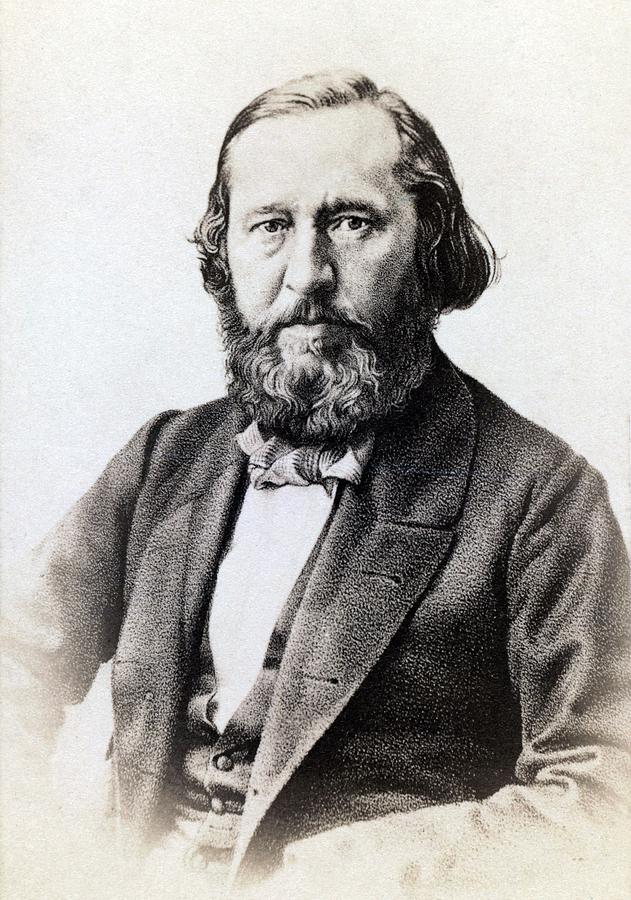

I came across Aksakov courtesy of George Borrow, whose book Wild Wales, I had just finished in an early twentieth century OUP edition. Listed in the back of the Borrow were other OUP offerings of the time including, in the autobiography section, Aksakov's Days of Childhood. I had never heard of the man and was intrigued that an apparently major author should have entirely escaped my attention; not that I had not read him, there are many I haven't read more famous than he (Charlotte Bronte to name just one), but that I had never even heard the name.

This gap in my literary knowledge is now partially remedied - I've read the first two volumes of autobiography and will shortly address the third - a memoir of the author's grandfather which was, I believe, the first of the family trilogy to be published. Never mind, I now know more than I did and I am exasperated by what I have found.

Aksakov is one of those writers whose quality of recollection I find astonishing primarily, I suppose, because this isn't a characteristic I share. He remembers and narrates not only minor incident after minor incident but also the emotional response they prompt and all this in provincial Russia at a time - in A Russian Schoolboy - when the war with Napoleon had just begun.

Not that Aksakov was either interested by or responsive to grand events. The only 'major news story' mentioned in Days of Childhood was the death of Catherine the Great which took place when Serge was five. Napoleon (and General Bagration) get a mention - more than one - in A Russian Schoolboy - but, as I said, they elicit little interest from the author.

To quote some lines from the end of the book:

"The year 1807 began, Russia was now definitely at war with Napoleon. A militia was enrolled for the first time in our history; young men crowded into the army, and some of the students, especially the pensioners, asked permission of the Government to leave the University for active service against the enemy; among these were my friend, Panayev, and his elder brother, Ivan, our lyric poet. I blush to confess that I never thought at that time of 'rushing sword in hand, to join the fray; ..."

Aksakov was no Tolstoy although I now gather he is at least a figure, some would say an important figure, in Russia's literary hierarchy; he does, however, share many characteristics with Proust - the high emotional response to minor events, being an extreme mummy's boy; a highly developed literary sense. He does not, however, share Proust's extraordinary ability to describe, even to caricature family, relatives, servants and friends nor does he share Proust's sense of narrative structure. Aksakov's book(s) is too linear, too formally chronological to the extent he apologizes on the few occasions when he goes off-piste off the timeline.

I mentioned exasperation. There are many occasions in the book when you feel all young Aksakov needs to bring him 'up to snuff' is a good slap. Massive enthusiasms: for fishing, shooting, butterfly collecting, acting - the next driving out the former with never a middle way. Huge fears: of being clasped by the hands of a corpse, of crossing a river whether or not in spate, of being parted from his home in the provinces, and above all, of earning his mother's displeasure or being separated from her - these and illness are the dominant themes.

Particularly his mother, always his mother.

I didn't like Aksakov's mother and I don't think he ever really saw her as she was. She was as terrified of being parted from him as he from her (despite the presence of a little sister and latterly, three other children). She hates the country (which he loves - one of their few areas of difference) and refuses ever to take part in running a household preferring to dream of 'society' and, when it suits her (so it seems to the reader) being ill to enforce her purposes.

Aksakov's description of first going to school in Kazam makes the point far more easily than I can. He is clever, well-read for his age and thus, despite being incapable of any concept of mathematics, is sent away to school despite his mother's major misgivings. He has his hair cut:

"When my father saw me, he laughed and said, 'Well, one would hardly know Seryozha again!' But my mother, who had failed to recognize me at the first moment, threw up her hands, cried out, and fell fainting to the floor. I cried out wildly and fell at her feet. ..."

He's to be a boarder but she visits every day, twice a day. Finally mother is persuaded to go home and, very quickly, he becomes ill - some thought it was epilepsy but the modern reader would be more likely to diagnose some form of acute anxiety syndrome - so mother returns (and these journeys are not short). And finally, after various Russian episodes of long cold runs on sleighs, crossing rivers with recalcitrant ferrymen and fighting with the school authorities, she takes Serge home and that's that for another year.

A Russian Schoolboy by Serge Aksakov, first English translation in 1917 (trans by JD Duff); my edition on Kindle.